Zero-drop and minimalist shoes became all the rage a decade ago when the best selling book Born to Run sparked a revolution in barefoot running. Inspired by the romantic idea of Mexican tribesmen running thousands of miles barefoot and fueled by nothing but corn beer, many runners binned their old shoes and started running in footwear that look like flip flops. The idea behind flatter, thinner shoes was that they would invite a forefoot or midfoot strike, which barefoot proponents claimed was more efficient than a heel strike and was less likely to cause repetitive stress injuries. 10 years on the hype has simmered down, and there are now several studies with which to fact check the claims made years ago. Armed with an internet connection and a desire to know the truth, this blogger did just that – went through some of the most recent research in search of answers.

Disclosure: I am a zero-drop runner and have been for several years. My own experience has been one of success, but, not wanting to rely on anecdotal evidence, I’ve done my best to consolidate the findings of several reputable studies and present these as objectively and accurately as possible. However, I have also relied on my own observations as well as those of other runners.

What are minimalist and zero-drop shoes?

In traditional running shoes, the heel is higher than the toe. In a zero-drop shoe, on the other hand, there is no difference in the height of the insole through the length of the shoe – that's zero drop from heel to toe. And a minimalist shoe is just a skinny zero-drop, one with very little stack height. If that’s still a little confusing, a closer look at the difference between heel drop and stack height might help clear things up.

Heel drop vs. stack height

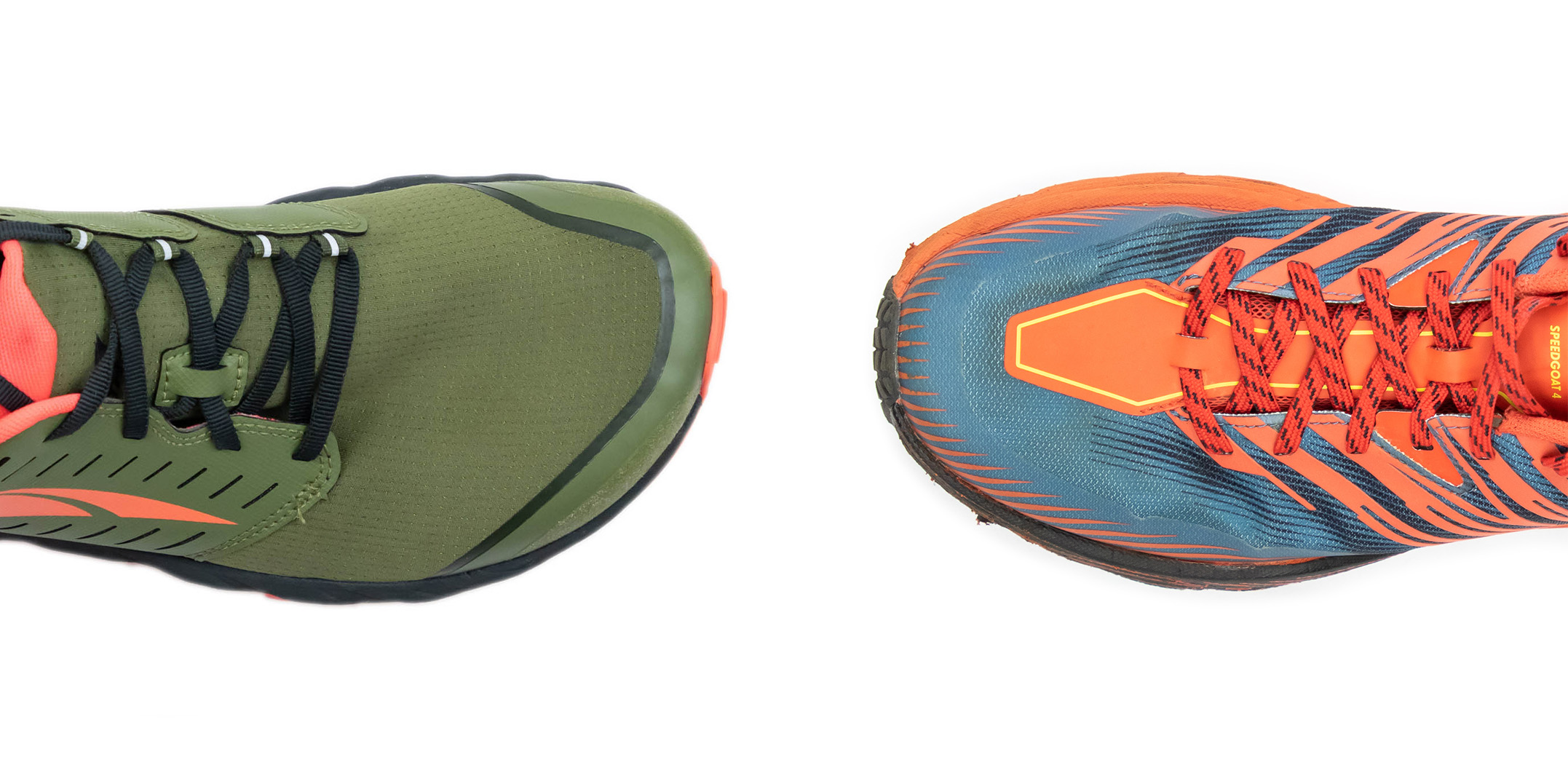

Besides a shoes’ outsole and toe box profile, there are two specs that most discerning runners will give careful consideration: stack height and heel drop. Stack height refers to the amount of material between the runner’s foot and the ground. Although this measurement includes the outsole and insole, it’s a good indication of the amount of cushioning in a shoe. In most shoes the stack height of the heel is higher than that in the toe.

Heel drop, on the other hand, refers to the distance in stack height between the toe and heel of a shoe. Traditional running shoes have more cushioning under the heel (where everyone once assumed it was most needed), which raises the heel by as much as 12 millimeters.

Zero-drop shoes

Zero-drop shoes can have a significant amount of cushioning, but, as the name implies, there’s no drop between the heel and toe. They have the same amount of cushioning right through the shoe from toe to heel. The Altra Lone Peak 5 (the shoe I do longer runs in) has a 25 millimeter stack height from toe to heel, making it a zero-drop. But it’s too beefy to be considered a minimalist shoe, which generally has less than 16 millimeters of stack height. It’s more of an all round trail runner and offers a good balance of cushioning, sensitivity, and low weight. Although it’s not in the definition, another common feature of a zero-drop shoe is a wide toe box, which allows a runner’s toes to splay out as they would if she were running barefoot.

Minimalist shoes

Minimalist or barefoot shoes have a low or zero drop and very little cushioning – 16 mm or less. The Merrell Trail Glove 5 is completely flat and has a stack height of only 11.5 millimeters, making it an average minimalist shoe. But shoes like the Vibram FiveFingers take things to the extreme with absolutely no cushioning (They don’t even look like real shoes). Some people refer to these as ‘barefoot shoes’, although that term is itself an oxymoron. Terminology aside, these are the closest you’re going to get to running barefoot while still having some protection between the soles of your feet and the trail. Like more generously cushioned zero-drop shoes, most minimalists have a wide toe box in keeping with the ‘natural is better’ design philosophy.

Is a midfoot strike really better than a heel strike?

The original idea behind flatter, thinner shoes was that they would encourage a forefoot or midfoot strike, which barefoot proponents claimed was more efficient than a heel strike and was less likely to cause repetitive stress injuries. Unfortunately for the early barefoot advocates, forefoot striking quickly proved to be impractical for distance running, and research into the mechanics of a midfoot vs heel strike hasn’t proven one to be more efficient than the other.

However, there is evidence to support the idea that heel strikers are more likely to suffer from injury. That is not to say that heels-striking is necessarily bad – just that heel strikers are more likely to land with the kind of excessive force that can lead to injury. If a runner has a habit of aggressive heel hiking, she can soften her footstrike by simply shortening her stride. In most cases this is enough to avoid injury. If shortening her stride doesn’t prevent a recurring injury, she should at least consider swapping to a midfoot strike. Unlike shortening your stride, changing your foot strike is not an overnight fix. Most runners who make the swap do so while transitioning from conventional shoes to zero-drops – a process that typically takes at least 3 months.

Research into running form might not have provided midfoot strike advocates with the support they were hoping for, but it did confirm what coaches and elite athletes had long suspected: that a shorter stride is more efficient than a longer stride and is possibly the most important aspect of good running form. When you strike the ground with your foot in front of you, you generate a force that opposes your direction of travel, even if it’s obliquely. The result is that less energy is converted into forward movement, and more energy is transmitted into your joints, where it can result in injury. By shortening your stride and landing over your foot, you avoid dispersing energy in this counterproductive way and instead use it to propel you forward.

What are the benefits of zero-drop shoes?

Where does that leave the proponents of zero-drop and minimalist shoes? Was it all just hype? Not at all. Flatter, thinner footwear does actually offer significant benefits, especially for trail runners.

Lower impact forces

The claim that zero-drop shoes can reduce the risk of injury by encouraging a mid-foot strike is mostly true, and I say ‘mostly’ for two reasons. The first caveat is that there are runners who use a heel strike with no problem. That’s because heel striking isn’t necessarily bad; only high-impact heel striking is. And that relates to my second caveat: a low profile heel will encourage a midfoot strike, but, as I’ve already explained, you can also achieve a softer footstrike by shortening your stride, something that you should be doing anyway. That said, if you would prefer to use a midfoot strike but are just a little too inflexible to land midfoot in regular shoes, zero-drops can help you get there.

Stability and control

Stability and control are important in trail running, and zero-drops help with both by encouraging a midfoot strike, which puts your midfoot and toe box into contact with the ground at the point of initial impact. This means more contact between your shoe and the ground, and more grip with which to slow yourself down or apply force laterally. It also helps that most zero-drop shoes have a wider toe box, which allows a runner to properly engage the ground with the only parts of your foot which are properly dextrous. The big toe especially is important for maintaining balance through the stance phase of a stride.

Comfort and foot health

Trail races can go on for much longer than the average road marathon, and they can be a lot more taxing on your feet. The wide toe box on most zero-drops allows your toes to splay out much like it would if you were running barefoot. The most obvious advantage of such a design is that it reduces the risk of hammer toes, bunions and plantar fasciitis, but it also improves general comfort - important when you’re going to be on your feet for several hours and they’re going to swell as they do over longer runs. When I first swapped to zero-drops, comfort was very low on my list of reasons to change, but as my runs got longer, a wide toe box became one of the most important features of that shoe.

Are there additional benefits to minimalist shoes?

By now the advantages of zero-drop shoes should be clear, but that still leaves a question about minimalist shoes: what does a runner gain by running in shoes that have no drop and little or no cushioning? Less cushioning means less support, less impact absorption, and less protection for rocks and other sharp features in the trail. There must be a good reason that runners will give these up.

Improved groundfeel

The average zero-drop improves stability, balance and control by offering a wider toe box and allowing you to use your whole foot when engaging the ground. Minimalist shoes take this a step further by improving stability (more about that in a second) and allowing for more accurate proprioception – that awareness of how you are in contact with the ground. With less cushioning in the midsole, minimalist shoes give you more feedback with which to finetune your connection to the trail. By allowing you to make these minor adjustments to your gait and step on the fly, minimalist shoes give you even better balance, traction, and control.

Even better stability

There are actually two advantages to a lower stack height. Even if a skinny midsole didn’t allow for better groundfeel, it would still make a shoe more inherently stable. The physics is simple. Taller objects like conventional shoes with a significant stack height are less stable, while shorter but similar objects like minimalist shoes are more stable. If you’ve ever owned a pair of platform shoes, you know exactly what I’m talking about. I prefer to run technical trails in shoes that have less stack height precisely because they make me feel so much more surefooted. The downside to such a design is that there is less to protect you from sharp rocks and other pointy objects underfoot.

Light weight

While weight is not one of the most important factors affecting shoe choice, it is still worth considering. Lighter shoes will contribute less to fatigue over a long distance and will allow for slightly more accurate foot placements when you grow tired. But, you should never sacrifice a supportive midsole for low weight. If you need cushioning, it should be a priority. Only go with a lighter, thinner shoe if you’re very sure you don’t need the support.

But I have narrow feet

This was my first thought when I unboxed my first pair of zero-drops. I immediately expected that my feet would slide around inside the shoes. And they did, a little. On technical trails, where I’d frequently have to put a foot down on a sloping surface, I’d notice that my feet would slide sideways inside the front of the shoe. On less technical sections of trail, they felt great, but that loose feeling got to me. So, with my next pair of shoes I went back to a narrow toe box and low-ish drop, thinking these would provide a better sense of control.

The tighter toe box solved the sliding, but then it didn’t actually improve overall control even on those techy trails. With my toes bunched together, I just didn’t have the level of ground contact and balance that I was used to. With my next pair of shoes, I went back to a wide (but not as wide as the first pair) toebox. This shoe, The Altra Superior, struck the sweet spot between too much and too little space, and has become my go-to for shorter, faster runs. That first pair of shoes (those with the toebox that initially felt too wide) remain my preferred shoes for longer runs (marathon length and longer).

Which is good for what?

It’s best to consider your needs and abilities before deciding between a pair of minimalist or zero-drop shoes. Those ultralight racers might shout “I’m all for speed”, but you need to ask yourself if your legs are up for it.

Zero-drop shoes

Contrary to popular belief, the average zero-drop shoe – one with a 20 to 25 millimeter stack height – is not a specialist shoe. True, you might have more to gain from swapping to a pair of flat shoes if you have a history of knee pain, but most runners can benefit from zero-drops if they’re prepared to make the swap. And by swap, I mean transition. If you’re running anything more than 15 km a week, it would be unwise to give up your old shoes cold turkey. To transition successfully, you’ll need to slowly decrease the amount you run in your old shoes and increase the weekly mileage you do in your new zero drops. My article on how to transition to zero drops goes into this in more detail.

Minimalist shoes

Unlike a zero-drop heel, less cushioning does not reduce your risk of injury. If anything, less cushioning increases your chances of injury, and runners should only consider a switch to a minimalist shoe if they meet certain criteria.

- No recent history of injury

- Well developed foot and leg muscles (seasoned runners only)

- Focussed on shorter distances

What do you have to gain? Better stability and ground feel. Admittedly, a thinner sole offers less protection from sharp rocks, but the gains in traction and balance are such that I prefer to do all my shorter, faster runs in shoes with a lower stack height (the Altra Superiors are borderline minimalists). The extra control is especially welcome on more technical trails.

Fancy shoes are not a magic bullet

The trend towards lighter shoes with lower heels has been driven by the belief that this type of footwear will help athletes run more efficiently while reducing the risk of injury. But that’s only partially true. It’s actually good form and strong muscles that improve efficiency and lower the risk of injury. Zero-drop shoes can help with both, but you’ll still have to focus on running with good form – midfoot strike, short stride, and good posture – to get the most benefit from a pair of shoes. And don’t forget, you have to transition.

Get more advice from this gearhead

You now know almost everything you need to know about minimalist and zero drop running shoes – they offer significant benefits, but not all of these are freebies. You will have to put in some effort. Whether or not transitioning is worth it for you is a decision only you can make. I transitioned to zero-drops several years ago and haven’t looked back. If you want to know what that involved, you can find a description of my transitioning strategy in my article on how to transition from conventional running shoes to zero-drops. Also please sign up for my monthly newsletter Trail Mail if you found this useful and you’d like to get more great running-related content delivered straight to your inbox.