Any sport that involves defying gravity is inherently dangerous, and bouldering is no different. Fortunately, you can mitigate the risks by learning how to spot properly. As important to bouldering as belaying is to rope climbing, solid spotting skills will lower the chances of injury, give your climbing partners the confidence they need to commit to sketchy top-outs, and improve your ability to tell good spotting technique from bad – something you’ll need to do to ensure your own safety. Like most important skills, these will take time and energy to master, but the investment will be well worth it – one the most important you will make in your climbing career.

Spotting basics

Before you can safely spot a climber, you need to know how to assess the fall zone, how to pad the landing, and how to guide a falling climber onto the pads.

Anticipate where and how a boulderer will fall

The first step to preparing the landing involves looking at the line being climbed and trying to determine the area covered by the fall zone, bearing in mind that the climber might not fall straight down. To better predict where a climber might fall diagonally or out and away from the wall, it helps to know how the climber plans to climb a problem. Many steep and awkward moves can result in the climber swinging or barn-dooring off the rock. Likewise, roofs and sequences that involve high heel hooks can raise the risk of the climber falling onto her back. In such instances, you need to be even more aware of objects that the climber could knock her head on in a fall. A proper analysis of these risks will help you to make informed decisions around pad placement and the positioning of spotters.

Pad and prep the landing zone

Having determined where the climber is likely to fall, you can now pad the fall zone, again keeping in mind the risks posed by different parts of the landing. If you are fortunate enough to have several pads to cover your fall zone, it’s a good idea to choose pads for different parts of the landing according to identified risks and priorities. For example, if you have a large, thick pad like a Black Diamond Mondo, it makes sense to put this under the top out (if it is high).

And, if there is a pointy rock embedded in your landing, it would be best to cover it with a pad that offers decent protection even across the hinge, or better yet, use a taco style pad. As for the soft, squishy pad that you wouldn’t want to fall on from any height – you can use that for the low roof start. If you don’t have enough pads to cover the entire landing zone, you will have to move pads while the boulderer is climbing. This can require some coordination, but more about that in a minute.

Communicate with the climber and other spotters

By the time you’ve padded the landing zone, you should already know which line the climber is going to attempt and have an idea of how she might climb it. But you might still have to coordinate responsibilities with other spotters. Deciding who is going to do what is especially important when one or more pads has to be moved while the boulderer is climbing. At least one spotter always has to be ready to catch the climber while the others move pads around. To make a mid-climb pad shuffle as smooth as possible, it helps to have a plan for which pads will be moved, where they will be moved to, and who will move them. Before the climber even leaves the ground, everyone should understand their roles and know who is going to do what.

Guide the falling climber onto the pads

The broad objective in spotting is to prevent the climber from injuring herself in a fall, with the prevention of a head, neck, or spinal injury being the highest priority. To lower the risk of both minor and serious injuries, a spotter needs to do three things: guide the falling climber onto a boulder pad; help her stay upright and land on her feet (if possible); and shield her head, neck and spine from objects that could cause injury. The best way to achieve these often depends on the potential for a head or neck injury and the need to guard against it.

The standard position for spotting is an offset stance, with one foot in front of the other, slightly bent knees, and hands raised to receive the falling climber. When the climber does actually fall, you will place your hands on her back and guide her onto the boulder pad with a firm push (not a shove). If she is falling more or less vertically and likely to land on her feet, you can aim for her lower or middle back, but if she is falling backwards and out of control, it would be best to push into her shoulders and force her into a more upright position as she lands. If there is anything that she could knock her head on, like a rock or tree, try to put yourself between the climber and that object.

Be vigilant and stay focussed

Spotting should be treated like belaying in that it requires your undivided attention. If your role is to catch the climber and not move pads, keep your eyes on the climber at all times while also being aware of rocks and stumps that you could trip over when you take a step backwards or sideways. Make a mental note of such obstacles before the boulderer starts climbing. You won’t be able to look for them once she has stepped off the ground.

Strategies for specific types of problem

In certain situations, you might need to adapt your approach to mitigate the risks associated with that kind of problem.

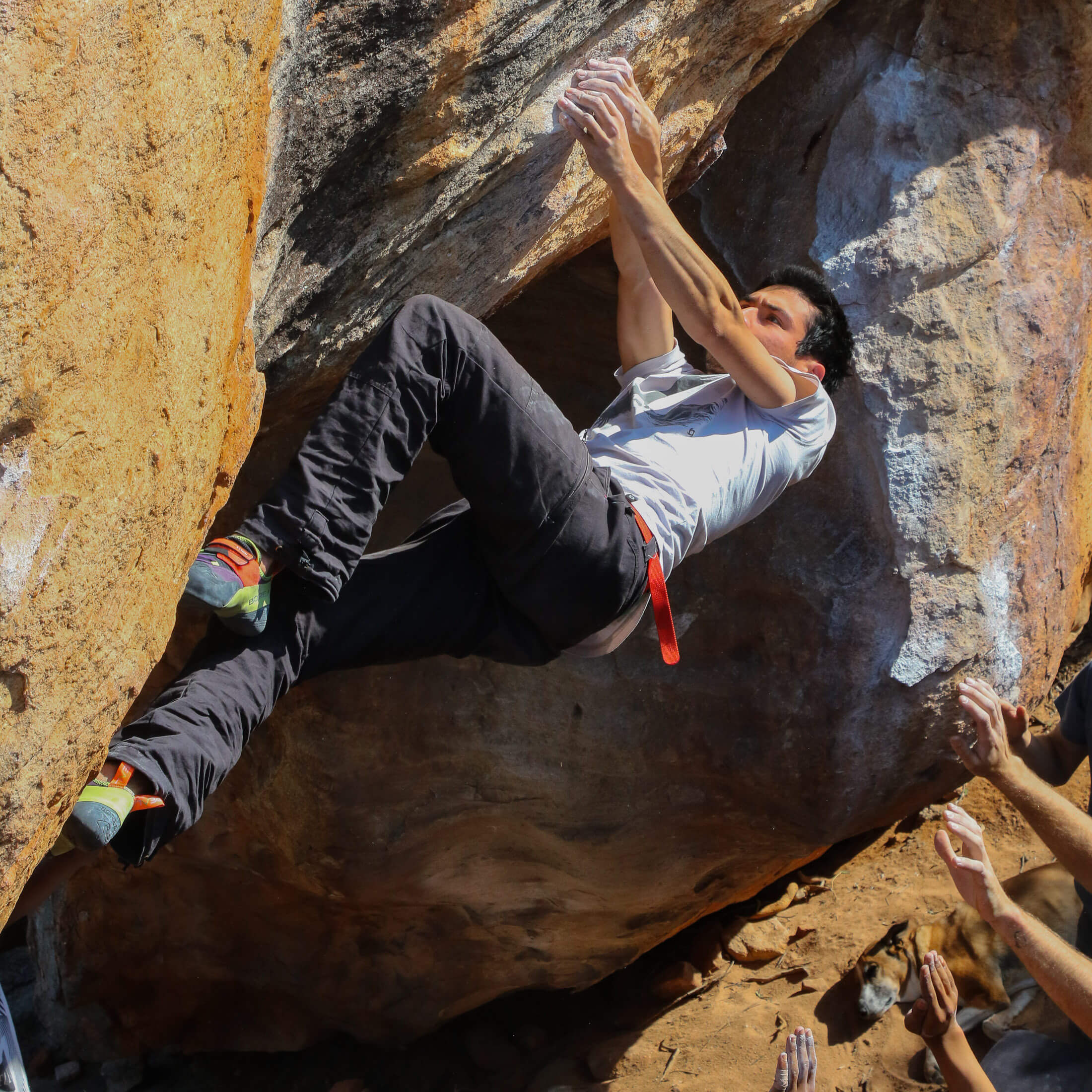

Roofs and steep boulders

Roofs and overhangs can require a climber to have her feet high – often level with her head or higher. This is not particularly risky if these moves are performed low down on a problem from where it is still safe for the climber to fall on her back. But once the climber is higher on the problem, spotters will have to try to push her upright in a fall so that she lands on her feet. To do this, you will need to slow the fall of her upper body by pushing into her middle or upper back. Just be aware that climbers are typically off balance when they fall from such positions and can come off the rock with arms flailing. Also be aware of flying feet when the climber cuts loose.

Slabs and low-angle boulders

Slabs and low-angle problems typically require a different technique as falls often involve the climber sliding down the rock instead of actually falling. If the climber does slide down the slab, be aware that she can trip over backwards if her foot catches on a feature in the rock or even when she hits the landing. Be ready to stop her from falling backwards into objects that she could knock her head on. If, on the other hand, the climber jumps away from the slab, aim to catch her around her hips and guide her onto the pads while ensuring that she stays upright.

Highballs

First off, the height of a highball – or at least the height that the climber falls from – makes a big difference to how you should spot a highball ascent. Above 20 feet, a climber is going to come down with too much force for a spotter to be able to guide them onto the pad. The most you can do in such a situation is make sure that the climber doesn’t fall backwards and into a rock or stump after landing on the pads. Given the size of the fall zone, it’s best to have a team of spotters to ensure that the perimeter of the landing is covered. A team spot also has its benefits at more moderate heights, where a group catch can ensure that there is always someone in the right position for guiding the falling climber onto the pads.

Spotting in the gym

The bouldering gym might seem like a relatively safe place, but you are as likely to suffer an injury climbing indoors as you are when bouldering outdoors. With a relaxed atmosphere and sprawling expanses of foam, gyms can inspire us to take bigger risks more regularly. When climbing outside, you’d probably check the placement of pads three times over and gather a team of spotters before committing to a heel hook traverse 15 feet off the ground, but you wouldn’t think twice about attempting the same problem in the gym. This overconfidence can be detrimental as it is possible to hurt yourself when falling from height regardless of how much foam you have underneath you.

That said, it is only recommended to spot a climber in the gym in certain situations. Why? Because the advantages afforded by spotters when outside – where they can prevent the climber from falling onto something that could cause injury (particularly an injury to the head or neck) – are offset by the risk that the falling climber might land on a spotter (more of a risk with inexperienced spotters but even possible with veterans). As for the situations in which it is always better to spot a climber, look out for these.

- When a climbers body is parallel to the ground or her feet are above her head

- When trying to execute a move that could result in the climber toppling backwards

- When jamming a foot into a recess or between two holds where it could be trapped in a fall

Get out there

The only way to hone your spotting skills is to actually put them to work. So get out there, befriend some experienced spotters who you can emulate and learn from, and strive to continually improve your skills. Besides lowering the risk of injury to your climbing partners, knowing how to give a good spot will allow you to more accurately judge the spotting skills of others, which in turn can help you choose partners who will do their part to ensure your safety. If you see rookie boulderers practising poor spotting technique, offer some guidance – making it clear that the advice is being given with the best intentions – and you’ll help make bouldering a little safer for everyone.