The fastest way to improve your climbing is not to train harder but climb smarter. And by ‘smarter’ I mean with better efficiency. On every route there are hundreds of opportunities to conserve energy, and if you can make the most of them, you’ll find that you have enough energy to pull through crux sequences that once spat you off. The biggest thing separately good climbers from mediocre climbers is good movement technique – gripping lightly, weighting their feet properly, using momentum effectively, and finding creative resting positions. Master these, and you’ll start crushing routes that you thought were well above your ability. Of course, if it were so simple, every seasoned climber would be climbing 5.13, and they’re not. So what is holding most climbers back? The short answer is a lack of good movement habits.

There are many aspects to good climbing technique, and if you had to think about all of them while actually climbing, your movements would be ponderous and slow. But if you make them a habit – as you can with practice – you will automatically climb with better technique and efficiency. It’s hard to overstate the importance of fostering such habits, but I’m not going to belabour the point. In Dave MacLeod’s book 9 out of 10 Climbers Make the Same Mistakes, he goes into the importance of good habits in much greater detail, and I strongly recommend that you read his book if you enjoy this article. Much of what I have written here was informed by MacLeod’s book, which in my opinion is the best ever written on the subject.

- Learned movement skills

- Quick and precise footwork

- Dynamic movement

- Energy moderation

- Resting and shaking out

- Breathing

Learned movement skills

When it comes to climbing technique, muscle memory is important for two reasons. The first is that it frees up some mental space during a move. This extra cognitive capacity can then be used to focus on the finer details of a move – how to weight your feet properly, how to twist a little further to extend your reach, how to hit the far left of a handhold with one hand so as to make space for the other. All of this would be much harder or even impossible if you had to focus all your energy on the move itself, as you sometimes have to when practising a certain movement technique for the first time.

The second reason is that muscle memory can help a climber execute a move more smoothly and with better muscle recruitment, both of which result in better energy efficiency. Of course, to realise the full potential of these benefits, a climber must also know which of the many possible movement patterns will be the most energy efficient. And the only way to know that is to be able to draw on one’s extensive experience of similar sequences or layouts of holds. This is why I say there are two components to good movement technique: an understanding of which move will be most efficient for a certain pattern of holds, and the muscle memory needed to execute it efficiently. Fortunately, you can train both at the same time.

Proprioception, memorisation, and review

To properly understand climbing movement, you need to be able to do three things: first, be receptive to the sensations of a movement, then memorise that feedback (this will happen almost simultaneously and automatically with practice), and finally, review it when you step off the wall. If you can do that, you can repeat a move several times with small changes to form and then compare the feedback to determine which of the versions felt the most controlled or efficient.

Some coaches and climbers call this process visualisation, but that definition is limiting and misleading. At the core of this technique, there is attention to the sensations of a move. The memorising of this feedback is automatic and will improve with practice, but you first have to pay attention to how a move feels if you’re even to have a chance of being able to review it later. Many climbers simply bare down on holds as hard as they can when pulling difficult moves. Nothing is learned this way. That’s why it’s often better to practise movement skills on boulders or routes a few grades below your limit.

Seek out your weaknesses and expand your skill sets

Almost every climber can benefit from expanding their skill sets into areas where they have little proficiency. Being able to climb a wide variety of terrain is especially useful to trad climbers, who have to be solid at crack and slab climbing as well as face climbing. But sport climbers and boulders can also benefit from expanding their repertoires and building on skills within a larger skillset, say face or steep wall climbing. This is especially true if you have come to favour a specific style of climbing and are now struggling with routes that offer something a little different.

We naturally prefer to work on our strengths and climb routes that showcase these. The problem with this tendency is that it leaves a climber with big skills gaps. The best thing you can do to improve your climbing is identify these weakness – maybe it’s overhangs or very techy routes – and start working on them. This is, of course, actually very hard to do. Trying something that we’re not good at is humbling and painful, so we naturally gravitate back to whatever it is we’re good at. But to become a better climber, one has to fight that instinct and make a real concerted effort at improving those aspects of your ability which are weakest.

Hone acquired skills

Improving your movement technique doesn’t only mean expanding your skillsets. It can also involve refining an existing one. Many climbers would benefit from going back to basics and practising their footwork (more about that in a minute) or honing a learned movement skill like flagged sidepulls, gastons, rockovers, or drop knees. If you’re thinking that you’ve never seen someone doing drills in the gym, know that you probably have but just didn’t know what you were watching. Watch how top climbers warm up and you’ll probably notice that many are very focussed on their footwork even when climbing very easy problems.

Quick and precise footwork

The more you can use your legs to aid upward movement, the more you can save the energy in your forearms for when you really need it. This is one of the most important aspects of efficient climbing. The chances are that you know your footwork isn’t great and that you would benefit from doing some footwork drills. But even if you consider yourself to be very proficient in technical climbing, you can find room for improvement by breaking your footwork down into its key components – where you put your feet, how quickly you can place them on the best part of a hold, and how much weight you put on each foothold.

Aim for silent precision

Footwork can be broken down into two phases. In phase one, you place your foot on the target hold – simple enough, except that you want to hit the best part of the hold on first contact and do this quickly. Here you have to be aware of the trade off between speed and accuracy. If you try to place your foot too quickly, you won’t get it right the first time, and you’ll have to readjust, which will only cost you more energy. So the priority is accuracy. Aim to be as quick as possible while still being precise.

Put maximum weight on your feet

Phase two involves keeping your foot steady on the hold and then standing up on the foot with confidence as you make a reach or move up the other foot. Doing this while thinking about gripping with your hands and moving upwards can often be difficult. But you can make it more automatic by making a habit of putting as much weight on your feet as possible when your attention allows for it. Of course, different rock types allow for different levels or friction, and you can expect to have to spend some time dialling in your footwork when climbing on a different type of rock for the first time.

Set up and execute hard moves quickly

Sometimes you can flow from move to move without too much difficulty, but many harder moves require you to place your feet higher than normal or on holds that are less well defined than you’d like them. This is called the set up. Maintaining such a position is often strenuous, which is why you want to set up and then execute the move as quickly as possible. The hardest setups start from a position where it’s difficult to take even one foot of the wall. In such situations, you have to bounce the foot onto the target hold – something that requires a great deal of precision. Learning to do this – setup and execute hard moves quickly – is essential for progressing to the higher grades.

Don’t just push with your feet

There’s a lot more to good footwork than being able to bare down on small edges. With the correct technique, you can also use your feet to pull you sideways or into the rock. Using your feet like this allows you to initiate moves from footholds that are not directly below you, and enables you to oppose forces that would otherwise result in you swinging off the rock (barn door). To use a foothold this way, point your toes forcefully down into the most incut part of the hold and pull it towards you. It helps to imagine that you are actually grabbing the hold with your curled toes.

You can’t climb well in the wrong shoes

There’s a prerequisite to being able to use your feet to grab holds, and that is that you have to have the right shoes. Insensitive, neutral profile shoes make it difficult to dig into the back of footholds and acquire any kind of purchase unless you’re pushing straight down on them. What you want in a pair of allround shoes is a slight downturn, which will allow you to dig into the slightest incut. Certain types of terrain, like cracks and slabs, might call for something more specialised like a malleable slipper or a high-top crack shoe, but a moderately aggressive asymmetrical lace-up or velcro-secured shoe will be the most versatile.

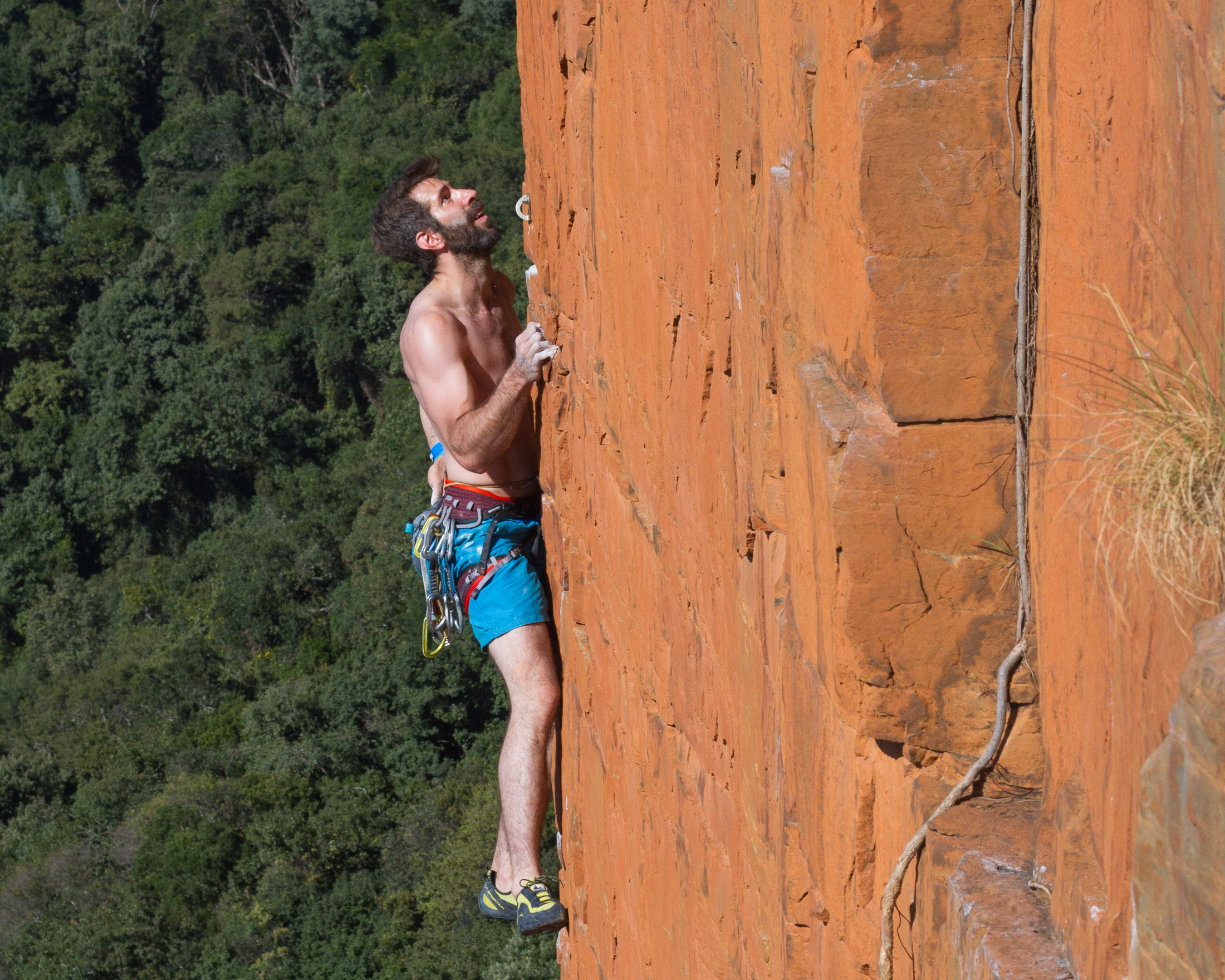

Dynamic movement

Climbing dynamically is always more efficient than climbing statically. True, there are occasions, like when you need to feel out a very small hold before engaging it properly, where a static reach is better, but there are more moves that can be climbed more efficiently with the proper use of momentum. I say the ‘proper use of momentum’ because there are two possible points of confusion around the words ‘momentum’ and ‘dynamic’.

The first is that some climbers only think of a dyno or deadpoint when they’re told to climb more dynamically. Dynamic movement is not limited to big moves. You can also make smaller moves more dynamic and efficient by generating a little upward momentum before making the reach – I’ll get to the lesser known techniques in a minute. The second point is that momentum does not refer to a continuous upwards movement. Unless you’re speed climbing, it’s just not practical to attempt a continuous upwards motion. Here I’m talking about momentum that is generated in a single move and is at the very most carried only as far as the next move.

A question of balance

It’s generally accepted that climbing ‘with balance’ means weighting your feet properly and being able to execute a move with a great degree of control. The problem is that there is a lack of consensus of what ‘control’ looks like. When many climbers hear ‘control’, they imagine being able to maintain a static position while making a reach. But if that were true, how many routes out there can be climbed with balance and control? Not many. What we need to do is expand on these definitions so that they’re more useful.

Static balance

When most people think of balance in the context of climbing, they think of static balance – that which allows you to make a slow, controlled reach. During such a move, you can usually pause and still maintain your connection to the rock. Moving this way is possible on easier climbs, but on moderate to hard routes, you’re likely to come across at least several sections where footholds are too awkwardly positioned to make slow movements possible or handholds are too small to hang onto with one hand.

Dynamic balance

When a slow hand movement is likely to cause you to lose your purchase on the rock, the solution is to bump that hand quickly between holds. Unlike a move made with static balance, a dynamic movement like this quick reach cannot be paused once initiated, and in many cases it cannot be reversed. Does this mean that these routes cannot be climbed with balance and control? No. If you can throw for and latch distant holds with consistency, you are still climbing with a degree of control.

It’s this more dynamic type of balance and control that you want to achieve. Besides allowing you to make reaches that just can’t be made statically, the use of momentum also allows you to make moves more efficiently. The physics is simple: It takes more energy to hold your mass extended above your center of gravity than it takes to throw your body beyond that low and stable base to an elevated position where it will be suspended in gravity only briefly. The key here is ‘briefly’. In addition to also using your leg muscles to effect upward motion, a dynamic movement doesn’t waste energy by holding you in an extended position longer than it needs to.

How to use momentum

Besides the obvious techniques – deadpoint and dyno – there are a dozen lesser known techniques for generating momentum in specific circumstances. Even though you’ve never heard of them, you’ve probably seen pros use these techniques to great effect in climbing videos.

Leg thrust

The leg thrust is the most basic momentum move in climbing and commonly used to power larger moves like a deadpoint or even a dyno. You set it up by hanging low from the handholds on straight arms and relaxed shoulders while keeping your feet still relatively high. To keep your center of mass close to the wall, you will have to bend your knees in a crouched position. To execute the move, you then push hard with your legs to thrust your body upwards and within range of the target hold.

Hip swing

The hip swing starts the same way as the leg thrust, but this time you create some lateral momentum to reach a hold that is off to the side. Start the move by swinging your hips from side to side like a pendulum. To get this going, it helps to pull with one arm while extending the other, and then alternate in a left-right-left-right rhythm. Then with the last swing, you thrust yourself out even further to catch the distant hold. It can take some experimenting to find the right plane for the swing, but when you get it right, this move can be made very efficiently.

Hip thrust

On steep terrain, executing a leg thrust from a backstepped position is usually easy enough. But if the feet are apart and your hips are squared up to the wall, things can get pretty awkward. Fortunately, the skilled climber has another movement technique in his repertoire: the hip thrust. This move involves dropping your hips away from the rock, essentially putting your butt out in space. To execute the move, you then thrust your hips inwards towards the rock, extending your reach. It can also be applied with a twist of the trunk, which usually gives one a little extra reach.

The roll

The roll is a good technique to employ when making a cross through move with the hand. It involves rolling the trunk on its axis to extend the reaching shoulder to the target hold. It’s usually not possible to generate enough rotational force with the legs alone, so to help initiate the roll, you use the leading hand (that which is about to make the reach) to pull the same side of your body inwards. The action is best described as a quick flick. Your shoulder will lead, extending towards the hold first, with your arm following once you’ve made the twist. If you try to make the reach too soon, your arm will only oppose the force you created to initiate the roll.

The shoulder thrust or head butt

On rock close to vertical, you might find yourself on holds so small that you can’t let go with either hand without falling off. In such situations, sticking your but out in space would put your mass too far from the wall and cause you to fall off. The only body parts you can really use for generating momentum are your shoulders and head. With your hips against the wall, lean your shoulders and head away from the wall slightly and then throw them inwards. The momentum generated will allow you a brief moment of weightlessness with which you can grab the next holds.

The arm swing

After you’ve made a big move, your trailing arm is usually quite low and not in a position to contribute to the next move. You could bring that hand to chest level before making the next move, but that would waste an opportunity to make use of a little bit of energy-saving momentum. Instead of immediately moving up your lower hand, wait until your feet are in position to make the next move and then reach all the way through to the next hold in one long continuous motion. To set up the move, let go of the lower hold and, drawing back your shoulder, drop that hand as low as possible. Then, to initiate the move, swing your shoulder and arm sharply upwards towards the distant hold.

The leg swing

The leg swing is a bit like the arm swing, except that you usually start with your feet high and off to one side of the handhold. When you take your feet off the wall, your legs will naturally swing in an arc underneath you. Ideally your next foot holds will be out to the side in the opposite direction – in the perfect position for you to take advantage of the swing and let momentum carry your feet to where you need to place them (quick and precise foot placement is essential). This technique is commonly employed in competition climbing and sport climbing on steep rock where it’s necessary to make big moves along diagonal lines.

Energy modulation

To climb efficiently, it’s essential that you modulate your energy, ramping up the power when it’s needed and then easing off when less strenuous moves and rests allow for a lighter grip. As with so many aspects of efficient climbing, you’ll need to make each of these a habit to improve your chances of implementing them properly during a climb.

Use a light grip

Over-gripping is guaranteed to rob you of energy when you need it most, and one of the best things you can do to improve your efficiency is to practise climbing with a light grip. Your ability to hold on with less force, is of course, also related to your ability to put more weight on your feet, and doing the two simultaneously while thinking about other aspects of movement requires no small amount of coordination. The best way to get better at this is to practise using heavy feet and a light grip at lower grades and in situations where you feel you can safely test the limits of friction. Make it a habit, and you’ll have a lot less to think about during a hard redpoint burn.

Ramp up exertion levels only when needed

There can be a huge difference in how much effort it takes to hang onto the wall from move to move, and if you don’t lighten your grip after a hard move or sequence, you’re going to waste energy that could be used to get you through the next crux. As you climb, constantly monitor how hard you are gripping and ease off where you can get away with holding the rock more lightly. You will probably also find that it pays to modulate your grip during individual moves as it often takes more energy to initially latch a hold than it does to stay on it.

Pace

Pace is another aspect of climbing economy that becomes increasingly important as routes get steeper and more difficult. While easy climbs on vertical to low-angled rock allow you to ascend at a relaxed pace, overhanging terrain demands that you pick up that pace so that you don’t spend more time hanging on with your fingers than you need to. Here your aim should be to climb as quickly as possible without any loss of technique. If your feet start skidding or missing footholds on first contact, you’ll need to dial back the pace a bit.

Climb relaxed

To conserve energy, you have to moderate muscle tension throughout your body over the course of a climb just as you would your grip. When you’re stressed, it’s all too easy to climb every move with your muscles tense when they should really be given a chance to relax. Obviously you want to stay calm and avoid feeling stressed in the first place (an ability that requires some training), but for most of us, it’s inevitable that moments of intensity will cause us to lose our composure. And that’s okay as long as we can bring our breathing under control again and relax muscles when we don’t need them to work so hard.

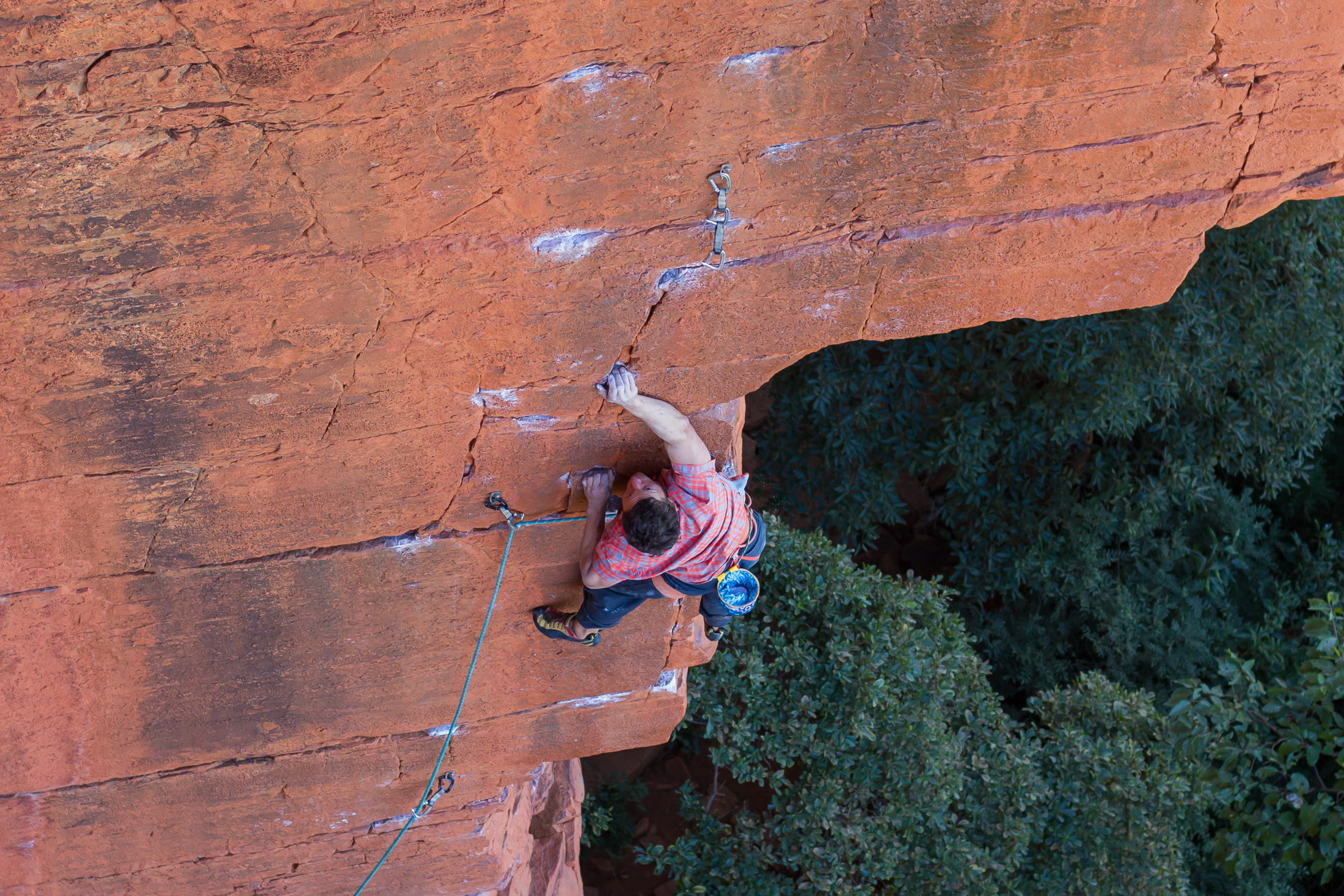

Resting and shaking out

Being able to make the most of every resting opportunity is key when climbing at your limit. Get better at resting in awkward positions and those that tax your core while giving your forearms a break, and you might be able to climb a grade harder even if you do nothing else to improve your technique.

Get creative

Creativity is key for finding less obvious resting positions. Trying to get something out of a less likely rest is probably not recommended on an onsight attempt, but if you’re working a route, you have nothing to lose and everything to gain by exploring all possible resting opportunities, and for the truly creative, these can be numerous. Kneebars, arm bars, hand jams, leg jams, perches, heelhooks, bat hangs – all of these can free up a hand for a shakeout, and some can even afford a no-hands rest.

G-tox

The G-tox method popularised by Eric J Hörst is an adaptation of the standard shakeout, a technique that you have probably already used to great effect. Much like a regular shakeout, the G-tox technique is designed to help remove lactic acid from your forearms, but unlike the standard technique, it does this with the help of gravity. Instead of simply dangling and shaking your arms, you alternate between holding your arm above your head and letting it hang, all while giving it gentle rotating shakes. Many climbers feel that this accelerates blood flow and recovery.

The mini shake

If you watch the IFSC, or even just good climbers at your local crag, you've probably seen someone do this. This technique is used to help reduce lactic acid build up in the arms when there is no place to pause and get a real shake out. Instead of stopping to shake out, the mini shake is usually employed mid-reach on a more easy move and is a good way to get a little back or just manage the pump when you want to slow down and read the next sequence.

Compose yourself when the rock only affords a mental rest

As you begin to push yourself on harder routes, some rests will serve more as mental rests rather than physical reprieves. Such positions usually don’t afford a proper rest. In fact, on some of these, you’ll grow more fatigued the longer you stay on them. So why pause if only briefly? In these situations, the goal isn’t to rest your forearms, but to slow your heart rate and compose yourself. With a clear head and a relaxed demeanour, you can climb through the fatigue, something you wouldn’t be able to do if you didn’t have your wits about you.

Know when to move on

Sometimes hanging out too long backfires, and resting becomes more work than it’s worth. As tempting as it can be, don’t linger too long. How long is too long? That depends on the resting positing and the level of recovery that it allows. Monitor the levels of fatigue in every part of your body as you shake out and consider which muscles need to be recharged for the next sequences. On rests that don’t allow you to get much back, it’s often best to move on once your heart rate is down and your breathing is under control.

Breathing

Poor breathing technique is one of the biggest and most common causes of sub-par climbing performance. Of course, it’s quite natural to hold one’s breath when stressed – which you’re likely to be when pulling through a crux sequence – but this response is the complete opposite of what you should do to conserve your energy and prolong your endurance during a climb. Proper breathing (with deep, slow belly breaths) is not only essential for delivering oxygenated blood to tired muscles. It’s also important for keeping a clear and focussed mind, one capable of reading sequences and executing moves with precision.

So how do you overcome the instinct to hold your breath when climbing hard? There’s a chicken-and-egg type conundrum here. When you feel stressed, you’re likely to breathe more shallowly or even hold your breath. But you also might hold your breath simply because you're pulling hard. The effects of oxygen deprivation on your mind would be the same, and you’d probably start to climb poorly and become panicky. The potential for a horrible negative feedback loop is obvious. So which do you address first, the stressed feeling or your breathing? The answer is both. It’s important to try to stay calm while also working on your breathing and getting your heart rate down. With consistent practice – at both proper breathing and mental fortitude – this will become habit, but at first you will need to remind yourself to breath and keep your cool even when under pressure.

Get out there

Climbing with efficiency is all about developing the right habits and is not something that can be achieved overnight. However, if you stick at it, month after month, you will realise a huge improvement in your climbing performance – far greater than you’re likely to achieve by training strength alone. So get out there and start honing these techniques. The improvement in your performance over just one season will have you crushing projects grades above your previous best.