If your rack can be compared to your social circle, then your carabiners are your oldest and most trusted friends. Ropes and harnesses will stay with you a few seasons at the most, and shoes – pfft, you’ll be tight for six months or less before you feel a need to move on. But carabiners are different. If you choose your carabiners carefully and look after them, they can become lifelong friends. Given how long they’ll be with you, you’ll want to choose your carabiners carefully. Luckily, you have found this – the most comprehensive guide to carabiners. Read on and you will find everything you need to know about these essential pieces of hardware and how to choose the best biners for different applications.

- Strength ratings

- Carabiner features

- Size, weight and functionality

- Carabiners for different applications

- When to retire a carabiner

Strength ratings

Almost every carabiner made today is CE and UIAA tested to ensure that it meets minimum strength requirements. That said, it’s worth paying attention to at least two figures – gate open strength and minor axis strength.

Major axis strength

This is the strength of the carabiner when it’s loaded along its longest axis, as it normally would be. Almost all carabiners have a major axis strength of at least 20 kN – a force far greater than you’re likely to subject your hardware to in the real world – and there’s little reason to choose one carabiner over another based on this specification. Again, any carabiner intended for climbing will be rated to at least 20 kN.

Gate open strength

When loaded with its gate open, a carabiner is typically much weaker than it would be when the gate is closed – something worth considering when choosing a carabiner for an application in which the gate might open accidently. Carabiners on quickdraws, especially those with solid-gate carabiners, are vulnerable to gate flutter, a scenario in which the gate is shaken open during a lead fall.

Minor axis strength

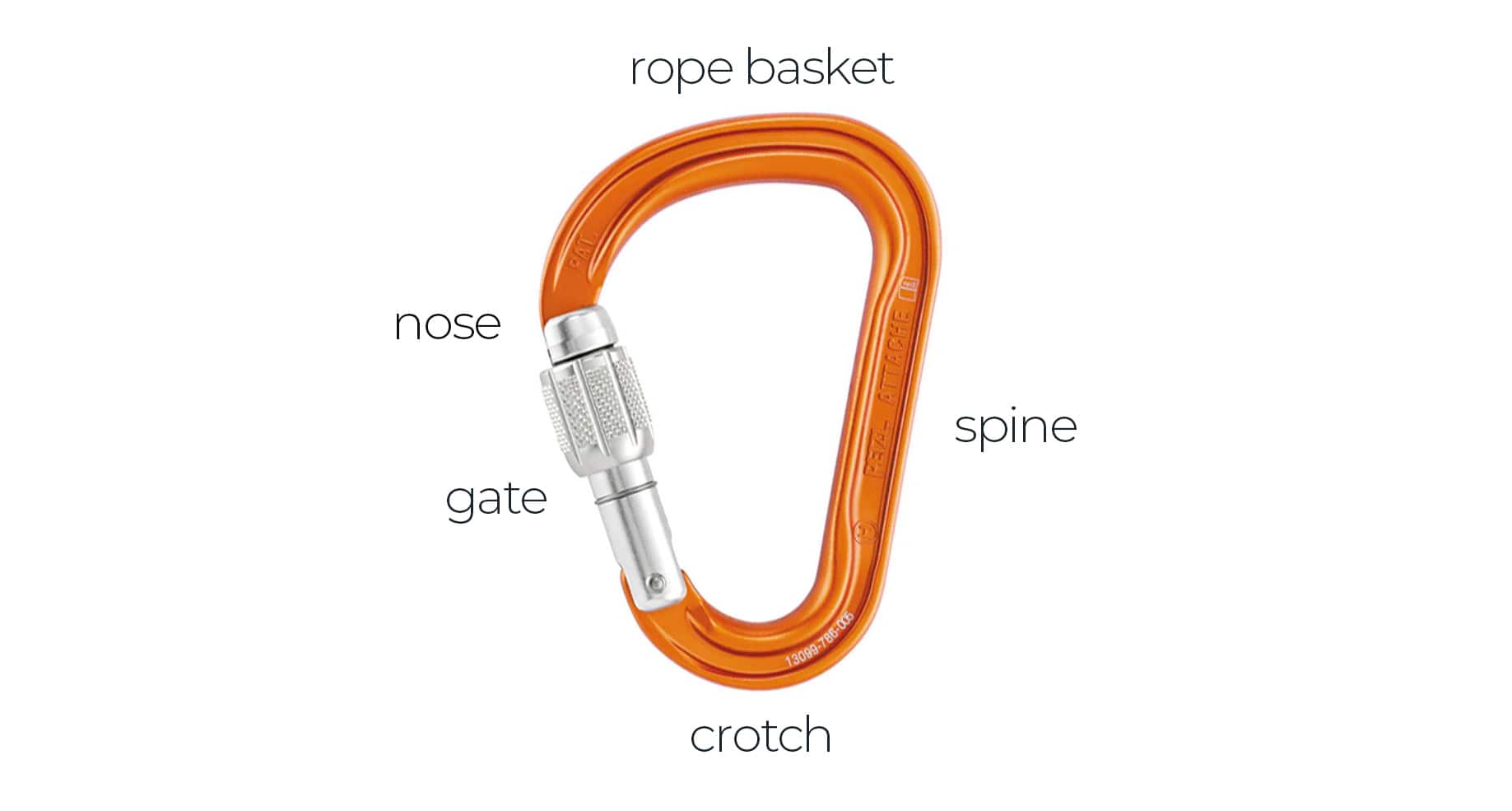

Minor axis strength refers to the strength of a carabiner when it is cross-loaded. A carabiner’s gate is significantly weaker than its spine, and most carabiners have a minor axis strength of only 7 or 8 kN, making failure a real risk if a carabiner is loaded across its gate. Most belay-specific carabiners are designed with this in mind and incorporate some kind of feature to prevent the carabiner from cross-loading.

Carabiner features

The three most important features of a carabiner are its shape, gate, and nose. In addition to these, some belay specific carabiners might also have some kind of anti-cross-load feature to prevent a carabiner from being loaded along its minor axis.

Shape

The shape of a carabiner affects its strength-to-weight ratio, gate opening, and general functionality. Along with gate type, this is the feature you should consider first when choosing a carabiner for a specific application.

Oval

The original carabiner design is weaker and heavier than more modern designs, but it retains some unique functionality – its rounded twin baskets make this the best design for mounting pulleys and racking nuts and hexes.

| Pros | Cons |

| wide baskets at both end | low strength-to-weight ratio |

Uses

- mounting pulleys

- racking wires and slings

Regular D

An evolutionary step forward from the oval, the regular D-shaped carabiner offers a higher strength-to-weight ratio by loading opposing forces closer to the spine. However, this type of carabiners is not as versatile as an asymmetrical D. Today regular D carabiners are generally reserved for heavy-duty rigging (search & rescue and other commercial applications).

| Pros | Cons |

| high strength-to-weight ratio | narrow basket (limited applications) |

| narrow gate (not particularly easy to clip) |

Uses

- building multi-point anchors

Asymmetrical D

The asymmetrical or offset D improves on the regular D by incorporating a larger gate and wider basket at one end. These features give asymmetrical D's much greater functionality in applications ranging from clipping to racking. This versatility, combined with a high strength-to-weight ratio, makes the asymmetrical D the most popular of all carabiner types.

| Pros | Cons |

| high strength-to-weight ratio | more expensive than regular D and oval |

| wider curved basket (greater versatility) | susceptible to crossloading |

| wide gate opening (easier to clip) |

Uses

- clipping into bolts and trad gear

- racking cams

- quickdraws

HMS (pear shape)

These oversized asymmetrical carabiners are almost always designed with a locking gate. Other features include a large rounded cross-section to reduce the friction and wear on a rope during belaying and rappelling, and a basket wide enough to comfortably seat two turns of a rope. Some HMS biners have an anti-cross-loading feature and are designed specifically for belaying.

| Pros | Cons |

| wide curved basket (greater versatility) | larger and heavier than other designs |

| wide gate opening (easy to clip) | expensive |

| available in a range of locking gate types |

Uses

- belaying and rappelling

- master point (in multi-point anchors)

Non-locking gates

Non-locking carabiners should make up the vast majority of your rack as they are lighter and less expensive than locking carabiners.

Wire gates

Wire-gate carabiners may look weaker than a solid gate, but most are just as strong as their solid-gate equivalents. And because their gates are lighter than solid gates, they’re also less susceptible to gate flutter (the opening of a carabiner’s gate under its own inertia). Their wide, flat gates are also a little easier to clip and are less likely to gunk up or ice up in adverse conditions. Their only downside is that most have a notched-nose design, which can make the unclipping of bolt hangers and wires a little more difficult.

| Pros | Cons |

| lighter than equivalent solid-gates | most use a notched-nose design |

| less susceptible to gate flutter | |

| less likely to freeze shut in icy conditions |

Uses

Any application where a notched nose will not be a disadvantage (can be negated by a clean-nose design).

Solid gates

Solid-gate carabiners are almost always designed with a keylock nose. This feature makes it easier to unclip a carabiner from certain types of gear, and many sport climbers will choose a solid-gate quickdraw for the ease with which it can be unclipped from a hanger. In the past, solid-gate biners were significantly heavier than their wire-gate equivalents, but technology has brought the weight of some high-end solid gates down to that of the average wire gate. Other than the slight weight difference, the only downside to solid-gate biners is that they are slightly more susceptible to gate flutter.

| Pros | Cons |

| utilises a keylock design | more susceptible to flutter |

| heavier than equivalent wire-gate |

Uses

- any application where a non-locking carabiner is called for

- clipping bolts (bolt-side biner in quickdraws)

Bent and straight gates

Bent gates make clipping a rope through the rounded bar a little easier, especially in the case of solid gates. This improved functionality means that bent gates are the go-to for rope-end biners on solid-gate quickdraws, while straight solid gates are typically used on the bolt-end of a quickdraw. Despite the prevalence of bent-straight combos in solid-gate quickdraws, this setup is not nearly as common in wire-gate draws. The flat, wide face of a wire gate is easy to clip, regardless of the shape, and straight gates are less prone to the accidental unclipping of rope or gear than the bent variety are. Still, there is at least one manufacturer that makes bent wire-gate carabiners.

Locking gates

The added security of a locked gate makes these the obvious choice in situations where an open gate could be disastrous. They come in a variety of sizes and designs, and are commonly used for applications ranging from belaying to anchor building.

Screwgate

The most popular type of locking carabiner is built around a gate which can be screwed open and closed. As the simplest design, this type of gate is most commonly used to secure small and medium lockers. In the past, most of these carabiners featured a notched nose, but today almost all screw-gates use a clean-clipping keylock design. Some models also feature a coloured band to warn of an unlocked gate.

| Pros | Cons |

| lighter than other locking gates | needs to be screwed closed manually |

| less susceptible to clogging by dirt than other locking designs |

Uses

- belaying and rappelling

- master point (in multi-point anchors)

Twistlock

The gate on this type of carabiner unlocks when twisted and then locks automatically as soon as it is released. These carabiners are typically heavier than their screwgate counterparts, but many climbers favour them as belay biners for their added security. Besides their weight, the only downside to twistlock carabiners is that they can be more susceptible to clogging if exposed to dirt.

| Pros | Cons |

| added security | heavier |

| expensive |

Uses

- belaying and rappelling

Nose type

When choosing carabiners, also look carefully at the nose. This design feature will determine how easily a carabiner can be unclipped from certain types of gear.

Notched

This design involves a notch that hooks behind a wire loop or bar in the end of a carabiners’ gate. The depth of the notch varies from biner to biner – an important factor to consider since it will affect how a carabiner handles. Shallow notches are not particularly troublesome, but deeper notches can snag on wires and hangers.

| Pros | Cons |

| allows wire-gate design (lighter) | more difficult to unclip from gear |

| less expensive than a clean-nose design |

Uses

- carabiners for racking wires (depends on personal preference)

- light racking carabiners

Hooded

In this design, the notched seat of the wire gate is hidden in a recess. The result is a carabiner that can be unclipped from gear more easily and weighs only slightly more than a regular wire gate. This type of nose is found on only a few high-end wire-gate carabiners, like the Wild Country Helium, and Petzl’s Ange S and Ange L carabiners, an innovative design that uses a single but thicker wire filament in place of the traditional elongated ‘U’ wire gate.

| Pros | Cons |

| allows for a wire-gate design (lighter | expensive |

| negates the need for a notch (easier to unclip) |

Uses

- clipping all kinds of gear

Keylock

This design does away with the notch in favour of a key-like nose that dovetails with a recess in the end of the solid gate. The result is a carabiner that is both strong and easy to unclip from hangers and wires. Today this feature is found on almost all solid-gate and locking carabiners. If you’ve wanted a reason to retire your old notched-nose carabiners, this is it.

| Pros | Cons |

| negates the use of a notch (easier to unclip) | none really |

Uses

- all solid-gate and locking gate designs

Anti-crossload mechanisms

Almost all carabiners are weaker when cross loaded – when loaded along their minor axis. To avoid such a scenario, manufacturers have come up with some innovative features to keep a belay biner properly positioned. Some of these are designed to keep a device like the Grigri from sliding down the spine while others are designed to trap the narrow end of the carabiner against the belay loop. And a few designs combine the two features.

Size, weight and functionality

There is a trade-off between size and weight on one hand, and functionality and durability on the other. Climbers prefer their gear to be light, which often means smaller, but they also need their gear to be easy enough to use and durable enough to withstand regular use. These last two factors have an inverse correlation with miniaturisation. If a carabiner is too small, it becomes fiddly or prone to wear and tear. When choosing gear, keep this in mind – prioritise functionality when weight isn’t important and try to strike a balance between light weight and ease of use when it is.

Weight

The weight of a carabiner is related to its size and gate opening, and you’ll have to make compromises if both size/gate opening and weight are considerations. But even among carabiners of the same size, there are some which are lighter than others. For example between carabiners with a 23 mm gate opening, there is a 5 gram difference. That might not seem like a lot, but if you multiply that by 35 (the number of carabiners in an average trad rack), you have a total weight difference of 175 grams – nothing to sniff at.

Size

Although closely correlated to gate opening, the size of a carabiner usually isn’t expressed in a specification. Still it’s something worth thinking about since a carabiner’s size can affect how well it handles as well as how much gear can be clipped into it. Some HMS’s have relatively modest gate openings but generously sized rope baskets. Likewise, some racking carabiners are quite small despite having decent gate openings. Note: the size of your hands also affect how easy it is to handle smaller carabiners. Climbers with smaller hands might not have any trouble with ultralight carabiners (especially if used with thinner ropes) while those with sausage fingers might find them frustratingly fiddly.

Gate opening

This is the metric that most experienced climbers look at when choosing racking carabiners. Although this spec gives an indication of how much gear a carabiner will hold, it’s most useful for getting an idea of how easy it is to clip gear into a carabiner. Of course, clipability also depends on other factors like gate type, but in general, a wider gate opening usually means easier clipping. Most full-sized carabiners have a gate opening of around 24 or 25 mm while the smallest carabiner has a gate opening of 18 mm. For racking carabiners that try to strike a balance between light weight and clipping performance, the sweet spot is 23 mm.

Carabiners for different applications

Different types of carabiners are better suited to different tasks. Here’s what to look for when choosing a carabiner for some of the more common applications.

Quickdraws and alpine draws

Quickdraws have designated rope-end and bolt-end carabiners, but the carabiners on alpine draws will likely be the same. Ensuring that each alpine draws has both a rope-end carabiner and pro-end carabiner creates extra faff that isn’t worth it when neither is likely to become scarred and put extra wear on the rope – the main reason you wouldn’t want to mix them up. However, when choosing quickdraws, you will want to take the following into consideration.

Rope-end

Rope-side biners need to be designed to readily accept a rope. The flat, square profile of wire-gates makes them easy to clip regardless of whether they are straight or bent, but the rounded bar of a solid-gate can make clipping more challenging if it’s straight, which is why solid-gate quickdraws have a bent gate on the bolt-end carabiner. Smaller carabiners and narrower gates can also make clipping more difficult especially when used with thicker ropes. When weight isn’t a priority, there’s no reason to go any smaller than a carabiner with a 24 mm gate opening, and for general trad climbing I also recommend trying to keep gate openings to a minimum of 23 mm.

Pro-end

What you need from your pro-end carabiners depends a lot on whether you are going to clip bolts or trad gear with them. If they’re going to be used for sport climbing, bolt-end biners need to be easy to unclip from bolts. Having a notched nose catch on a bolt hanger can be very frustrating especially while you are trying to clean draws off a steep route. To avoid this problem, choose quickdraws that have a solid-gate or clean nose wire-gate on the bolt-side biner. For trad climbing a clean-clipping nose is less of a priority as you are less likely to clip bolts. Also, even if a notched carabiner can catch on a wire, this usually won’t hold up a climber in the same way that it might if it was used to clip a steep sport route.

For a list of recommended draws, see my gear guide on quickdraws.

Belaying and rappelling

There was a time when climbers could only choose between similar HMS carabiners when looking for a belay biner, but today there are many tricked-out models designed to give you a safer, smoother belay. Of course, these specialist biners are not without their drawbacks. While they offer a clear advantage in eliminating cross loading, they’re not easy to stow on a harness and are not particularly light.

These downsides won’t affect you if you’re only going to use a biner for single-pitch sport climbing, but they could be a factor if you were going to use the carabiner for trad climbing or multi-pitch climbing. In this case, the lightweight simplicity of a regular HMS might serve you better. Alternatively, you can get a carabiner like the Petzl Attache Bar, which has a removable anti-crossload feature and give you the best of both.

- Black Diamond GridLock screwgate (Buy at REI)

- Mammut Smart HMS (Buy at Backcountry.com)

- Petzl Attache Bar (Buy at REI)

Racking gear

Unlike carabiners used for other applications, the main purpose of your racking carabiners is not to connect gear but rather to store it on your harness.

Cams

Choosing carabiners for cams is a little more complicated as it’s unlikely that you will only use these carabiners for racking. Although the norm is to extend cams with quickdraws and alpine draws, many climbers clip straight into the carabiner on a cam when the route takes a more direct line. If you anticipate using your cams this way, you’ll want to give some thought to the clipping action of the carabiners on your cams. Ultralight carabiners can help you bring down the weight of your rack, but smaller carabiners can make it more difficult to get the rope (especially a single rope) through the gate.

For general trad climbing, I recommend wire-gate carabiners with a gate opening no narrower than 23 mm. Only go smaller if low weight is a priority as it might be when you take a fast and light approach to your climbing. Lastly, you should match the colour of these carabiners to their cams to make it easier to select the right cam from a gear loop.

- Black Diamond LiteWire rack (Buy at REI)

- Wild Country Helium 3.0 rack (Buy at REI)

- Trango Phase Matte rack (Buy at REI)

Nuts

When choosing carabiners for racking nuts, the most important factors are shape and size. Some climbers use regular asymmetrical D biners for racking their nuts, but many others prefer oval carabiners for their wide baskets, which make it easier to spread out wires (usually six to eight on a biner) when they’re trying to select one. Nose type is also worth considering. Some climbers like a snag-free keylock nose while others prefer how a notched nose stops wires from being jettisoned out of an open carabiner. You might need to try both to figure out which works best for you.

- Black Diamond Oval (Buy at REI)

- DMM WallDO (Buy at Backcountry.com)

Anchor master points

To excel as a master point, a carabiner needs two things: a gate opening wide enough to accept a clove hitch, and a rope basket large enough to accommodate both the hitch and a few carabiners – You might need to clip your belay device and even your partner's PAS into your master point biner. For this purpose most medium to large HMS carabiners are suitable choices. These need to be locking, but a simple screwgate will suffice.

- Black Diamond VaporLock Screwgate (Buy at Backcountry.com)

- Mammut Classic HMS (Buy at REI)

- DMM Phantom HMS (Buy at Backcountry.com)

Other secure connections

There are several situations where a climber might need to create a secure connection using a locking carabiner but don’t need anything as big an HMS. Securing yourself to the top anchors using a PAS is one such situation, and building a two-piece anchor is another. But there are many more. In these instances a more compact locking carabiner might be easier to clip into a bolt shared with other hardware, and it can shave some weight from your rack, especially when consider that you’ll probably carry two or three of these smaller lockers on a trad route of multi-pitch sport climb.

- Black Diamond HotForge screwgate (Buy at REI)

- Petzl Sm’D screwgate (Buy at REI)

- DMM Phantom screwgate (Buy at REI)

Pulleys & ascenders

Pulleys work best with carabiners that have round, uniform rope baskets, and that usually means an oval locking carabiner. The same goes for ascenders which require the top carabiner to be clipped through two parallel holes, as it is with most handled ascenders.

- Black Diamond Oval (Buy at Backcountry.com)

- Petzl OK oval (Buy at REI)

When to retire a carabiner

The sharp edges of a rope-worn carabiner can actually desheath or even sever a rope. You’re unlikely to get this kind of wear on a biner unless you subject it to repetitive and intense wear, but it’s something you should be aware of. If you top-rope on the same piece of gear repeatedly or leave it up on a project for a long time, check it carefully afterwards. Carabiners that look like this should be replaced.

Microfractures. They’re kind of like Bigfoot. Everyone has an opinion, but no one has actually seen one. The belief was that if you dropped an aluminium carabiner from a height, it would develop one of these insidious and invisible cracks. But this simply isn’t true. At least three labs have conducted tests on dropped carabiners, and in every one, the findings have been the same: a single drop (even those from over 100 feet) did not weaken the tested carabiners (all UIAA-rated aluminium carabiners).

Get more advice from this gearhead

You now have everything you need to know about belay devices. But don’t stop here. On this website you’ll find many more in-depth gear guides on everything from belay devices to rock shoes as well as many more how-to articles. You can find these under the different sections in the categories menu, or, better yet, sign up for my newsletter to get all the latest from Trail & Crag delivered straight to your inbox.